Animal Rights and Punk > Non-Domination: World-Administration as Illusion

On Human Overreach, Negated Freedom, and the Anarchist or Anti-Domination Necessity of a Break Beyond Political Camps

The disenfranchisement of animals does not begin where they suffer under the consequences of human faunacidal actions. It does not begin with the physically normalized torture we call “exploitation,” nor with violence, nor with destruction.

It begins much earlier, pre-symptomatically, with human overreach into the world.

This overreach is not a single historical error but a civilizational operation: the assumption that the world is available, that its meaning can be defined by humans, and that freedom is primarily—or exclusively—a human attribute.

In this grasp, animals do not appear as independent existences, but as components of an order claimed by humans. This is the original disenfranchisement.

- Overreach as an Ontological Prerequisite

Humans have not merely situated themselves in the world. They have placed themselves above it. Ontologically, the world becomes an object. Politically, humans become sovereigns. Philosophically, meaning becomes something derived from humans. Normatively, freedom becomes a human monopoly.

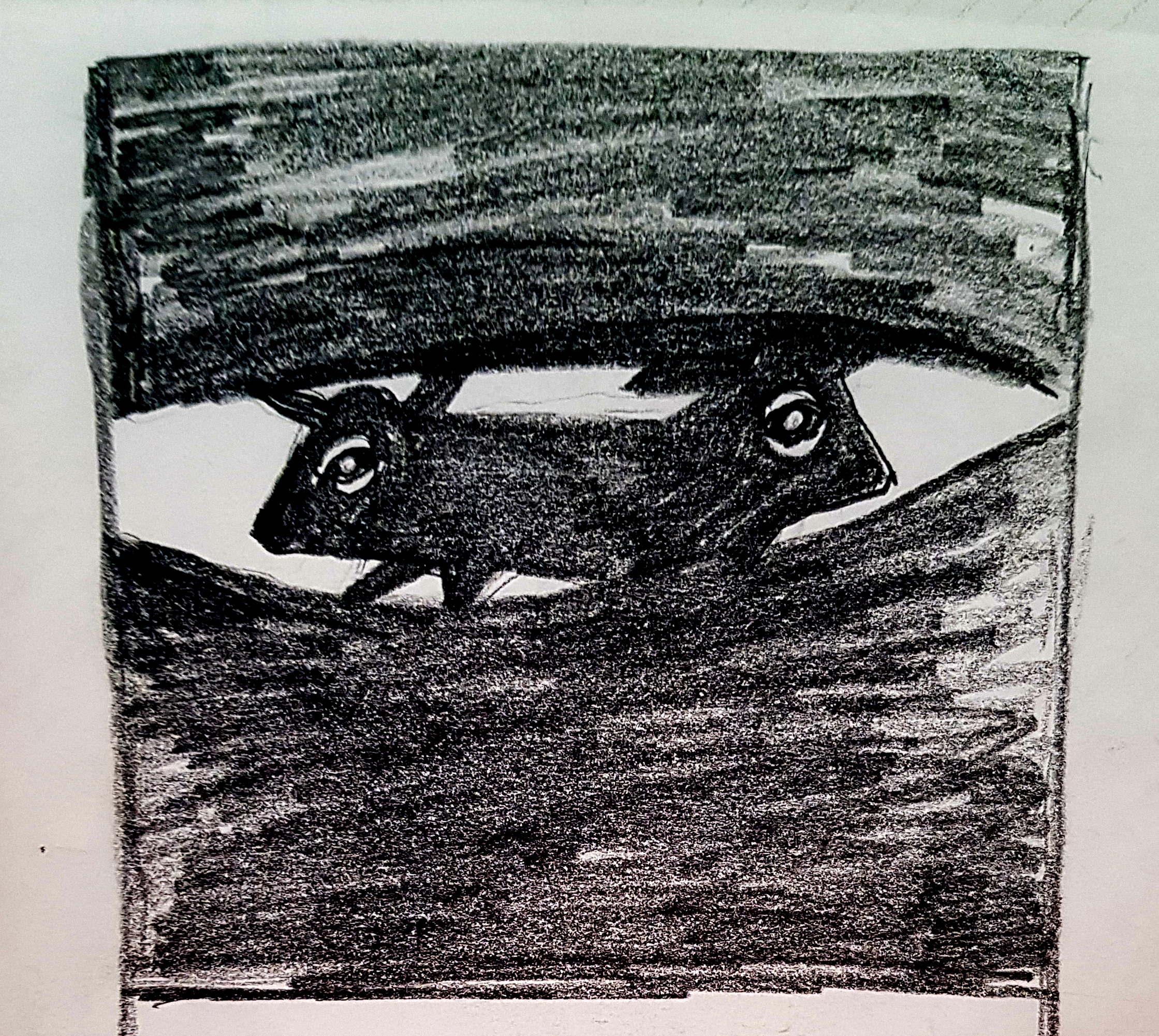

In this act, animals are not explicitly negated—they are de-worlded.

Their independence is not denied; it is simply not acknowledged. They appear as resources, as disturbances, as functions, or later as moral problem cases. Every further act of violence presupposes this initial appropriation.

Step by step, across cultural histories, a process of negation unfolds: animals are first removed from social, cultural, and worldly contexts (desocialization), then reduced to biological, symbolic, or functional categories (biologization/objectification). These processes consolidate the notion that animals exist outside the human-defined world, making their disenfranchisement normalized and invisible.

- Why the liberal animal rights discourse sets in too late

The liberal animal rights discourse is considered progress because it protects animals, recognises suffering and formulates rights. But it sets in after the transgression.

It asks:

- How should humans treat animals?

- How can violence be limited?

- How can use be morally regulated?

It does not ask:

- Why do humans believe they have access to animals as distinct beings capable of freedom?

- Why is human meaning-making considered authoritative?

This leaves the problem-causing worldview untouched. Access is not questioned – only pseudo-civilised.

- Rights without recognition of freedom are administration

In liberal approaches, animals are granted rights because humans grant them these rights without being aware of their own causal transgression of boundaries. These rights are conditional protective rights, welfare rights, defensive rights against some forms of instrumentalisation. However, a philosophically serious concept of rights cannot arise from care. It arises from a basis of recognition of the capacity for freedom independent of one’s own paradigm.

Capacity for freedom here does not mean autonomy in the humanistic or Kantian sense, nor self-rule, nor rational self-legislation. It means self-causality, self-reference and the existence of a relationship to the world that is beyond human control.

Animals are capable of freedom because they:

- have their own logic of action,

- develop their own social orders,

- act in relationships, conflicts and dependencies,

- cannot be limited by human concepts of domination.

This capacity for freedom is primary. It exists prior to any human attribution. Rights that do not recognise this freedom, but only regulate suffering, are not recognition – they are existential legal management.

- The Necessary Shift in the Concept of the World

Recognition of animal freedom requires a shift in the entire concept of the world, and thereby in the self-definition of humans, animals, and meaning.

The world is not a neutral space whose significance emerges through human interpretation. Its meaning is not available to us. We cannot possess it. Humans do not stand before the meaning of the world—they stand under it.

In this context, freedom does not mean imposing meaning, but not being derivable from a single framework of meaning. Animals exist in a world whose significance escapes human totalization. Their autonomy consists precisely in their world-relation not conforming to prevailing human categories.

The appropriate human stance is therefore not control, not care, not administration, but loyalty and friendship toward a world whose meaning surpasses us.

- Speciesism in a friendly guise

Liberal discourse distances itself from overt speciesism, but reproduces its structure:

- Humans remain the norm-setting centre.

- Animals remain normatively passive.

- Freedom remains anthropologically prioritised.

Animals are no longer despised, but protected with reservations. No longer disregarded, but cared for with reservations. This is not a break with speciesism, but a structurally paternalistic update.

- The reduction of animality – pro-animal and anti-animal

Both animal-hostile and animal-friendly worldviews share a basic assumption:

Animality is located outside the actual world.

Either as:

- a resource,

- a disruptive factor,

- or a moral appendix and special case.

What is missing is the recognition of animality as a social reality, as an equally original component of worldly contexts of meaning. Thus, even the pro-animal discourse becomes a variant of the same reductive worldview that produces hostility towards animals. The worldview remains identical – only the tone and intention change.

- The left-right dialectic as deprivation of liberty

This perspective also reveals why the classic left-right dialectic has reached its limits. Despite all their differences, both camps operate within the same basic framework:

- The world as available

- Meaning as defined by humans

- Freedom as hierarchically assignable

The right openly legitimises the deprivation of the capacity for freedom – through order, naturalisation, property rights. The left problematises it morally – through protection, care, administration. Both sides share the assumption that the capacity for freedom can be deprived, limited or allocated. The dialectic thus revolves around the administration of deprivation, not its revocation.

As long as political camps are prioritised over a worldly perspective, they are allowed to impose philosophically restrictive worldviews: rigid orders of meaning in which freedom is either monopolised or regulated, but never fundamentally shared.

- Why a break is necessary

A break is inevitable. Not a break from every single position wherever it is morally defensible, but from the assumption that political camps could be the final authority on questions of co-world ethics.

Our question is therefore

Not: How do we position ourselves on the left or right with regard to animals?

But rather: Why do humans claim the right to deny other their capacity of freedom in the first place?

Rights can only be meaningfully established where the original transgression is not taken for granted, but is radically problematised.

- Beyond friendly administrative management

What is needed is not better protection and finer morals, but a different way of thinking:

- Freedom not as human property,

- The world not as a human project,

- Rights not as an afterthought.

As long as the world view remains the same, violence will remain too – more polite, more legal, more philosophical, but not abolished. The alternative is not:

friendliness instead of violence. But rather: recognition instead of recourse. Only then will something begin that deserves this name.